Resources

INTRODUCTION TO COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE INVESTING

Investing in commercial real estate can be a valuable addition to any investor’s portfolio, offering various levels of involvement depending on individual preferences and expertise. For those willing to take on the responsibilities of direct ownership, managing and operating a property requires specific skills and a hands-on approach. Investors seeking liquidity may find publicly traded options like REITs or real estate-focused mutual funds to be the most suitable choice. Meanwhile, private equity real estate investments (such as those offered by Hightower Real Estate Partners (HREP”)) provide a compelling balance of income and growth potential for those who prefer a more direct yet passive approach.

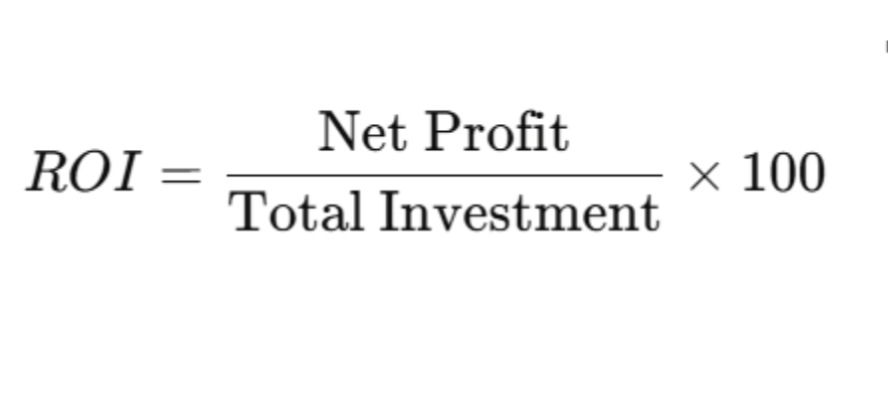

The private equity investment model is a powerful tool for wealth building, offering a risk-adjusted approach to financial security. Investors leverage real estate to save for significant life events such as retirement and education expenses, benefiting from three primary components:

- Equity Growth – As debt is repaid, investors build ownership in the asset.

- Appreciation – Over time, property values tend to rise.

- Cash Flow Distributions – Rental income provides consistent, passive income.

- Tax Benefits – Depreciation – Investors can deduct the cost of wear and tear of real estate over time or immediately, with accelerated depreciations techniques.

This muliti-pronged approach often results in higher after-tax returns compared to traditional investments like stocks and bonds.

Inflation Hedge

Unlike annuities, bonds, or other fixed-income products, real estate serves as a natural hedge against inflation. Historically, property values and rental income have outpaced inflation, allowing investors to maintain and increase purchasing power over time.

Low Correlation to Public Markets

Real estate investments are backed by tangible, hard assets, helping to limit downside risk. Unlike stocks and bonds, real estate is largely independent of market volatility, making it an ideal diversification tool in a well-balanced portfolio.

The Investment Life Cycle of Commercial Real Estate

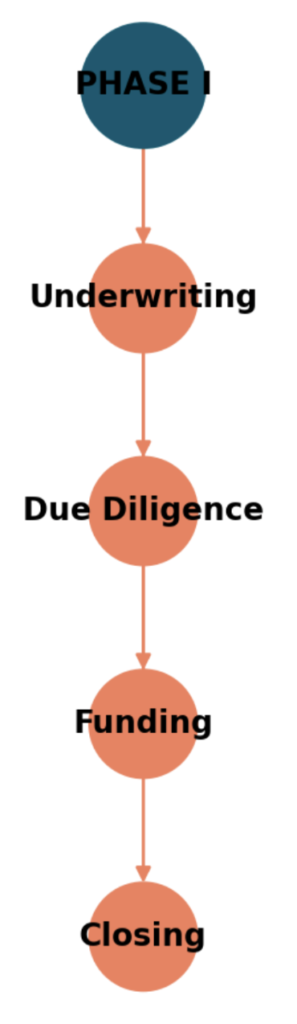

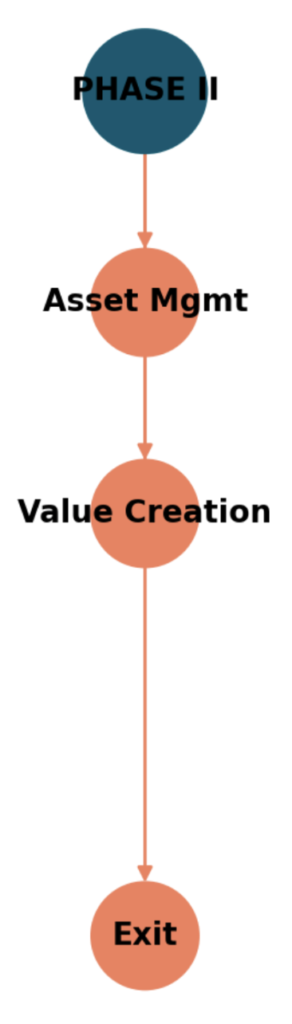

Understanding the investment life cycle is crucial for any CRE investment. The cycle spans from acquisition to exit and can be divided into two key phases:

- Initial Acquisition: Underwriting & Closing Phase (UCP)

- Value Add Phase: Investment Hold & Exit (IHE)

The Underwriting & Closing Phase covers the identification, evaluation, underwriting, and acquisition of a property. The Investment Hold & Exit Phase represents the time a property is held as an investment and the eventual sale. While UCP follows a standardized process, the IHE phase varies significantly based on the investor’s strategy.